Computing Space and the Architect As Spatial Coder

The convergence of virtual reality, blockchain and artificial intelligence has allowed for a new ontology of space to emerge.

When space becomes computable and computers become habitable.

Essay written for the Introduction to Contermporary Architecture class as part of the first semester of my MArch at the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SciArc)

Young architects can change the world by not building buildings - Virgil Abloh (1980-2021)

The convergence of virtual reality, blockchain and artificial intelligence has allowed for a new ontology of space to emerge. A space that is both computable - produces datasets that can feed into computing operations - and that itself has the ability to compute - a space that can take data and run operations in and on itself. I will refer to this computing space as the metaverse or Web3 indifferently, and will argue that architects need to become coders if they want to have a future role as active designers and builders of such emerging new computing spaces.

Introduction

Up until now, the relationship between the metaverse and architecture has occurred mostly at the aesthetic level, and only within the context of virtual reality. Little discussion about the potential implications of blockchain beyond the visual has been explored by architects. Despite the explosion of NFTs (non-fungible tokens) linked to digital art, the vast majority of these tokens are being used uniquely as a quick and easy monetization tool. Artists, and who can blame them, have jumped on the NFT bandwagon to promote and monetize their art, with very few fully exploring this new technology.

In architecture specifically, implementations of the blockchain and NFTs have also been literal at most. The recent show “Proof of Stake - Technological Claims” at the Kunstverein Museum in Hamburg, Germany, this November is a good example of the superficial level at which these explorations operate. Despite ambitious intentions, participating artists embraced blockchain with a fascination that is both naive and dated. Participating British artist Simon Denny - well known for his work with AI - minted NFT-representations of specific objects, and gifted them to participants as partial compensation for their work. His performance felt flat of cultural commentary, and reminisced of antiquated “how-to” explainers of the technology.

In the meantime, a much more exciting conversation is happening in between video games and crypto trades, in garages across the world, powered by blockchain mining operations, run by cybernetic anarchists, libertarian activists, opportunistic gold-diggers and gamblers, anonymous artists, and Silicon Valley converts.

The conversation is taking place within and about the metaverse, the new incarnation of the internet realized through the growth and convergence of augmented and virtual reality (AR/VR), advanced networking (e.g., 5G), geolocation, IoT devices and sensors, distributed ledger technology (e.g., blockchain), and artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML).

The conversation within the metaverse is equally at ease discussing technical algorithms, philosophical and phenomenological questions, and political systems. Within the metaverse, it all comes together in one of the best contemporary examples of cultural project versus practice, carrying profound philosophical, ontological, and aesthetic consequences.

The Metaverse

There is still no universally accepted definition of the metaverse, except maybe that it is a fancier successor to the mobile internet. Silicon Valley metaverse proponents sometimes reference a description from venture capitalist Matthew Ball:

The Metaverse is a massively scaled and interoperable network of real-time rendered 3D virtual worlds which can be experienced synchronously and persistently by an effectively unlimited number of users, and with continuity of data, such as identity, history, entitlements, objects, communications, and payments. – Matthew Ball, Metaverse Premier

If this definition reads as dense and cryptic, it is because the metaverse is rich and technical. We can think of the metaverse as a “quasi-successor state of the mobile internet’. While the mobile internet provided almost everyone with continuous access to compute and connectivity, the metaverse builds on top of the mobile internet layer by placing everyone “inside an ‘embodied’, or ‘virtual’ or ‘3D’ version of the internet and on a nearly unending basis”.

The metaverse allows us to inhabit the internet, rather than access it, and transforms the internet into a computing network that is spatial at its core made out of billions of interconnected computers. A giant distributed computer that can be inhabited: computing space.

Post-digital architecture and cyberspace

New media do not take us into uncharted waters, but rather confront us with the deepest and oldest questions of society and ecology: how to manage the relations people have with themselves, others, and the natural world. – John Durham Peters

Serbian architect and theorist Branko Kolaveric suggests in his book Architecture in the Digital Age that the post-digital context is defined by a shift from a fascination with the digital toward the simply architectural and the integrative. He argues that “there is less need for inventing new software tools, adapting hardware gadgets to architectural applications, and exploring novel forms that are vaguely habitable. Rather, the suggestion is that those with expertise in computational design embrace research agendas that explicitly address critical social issues and challenges of our era that are amenable to architectural solutions” in the words of Mark Clayton.

What Kolaveric (and Clayton) fail to recognise is that the “digital” is not a static entity, but rather a dynamic body of techniques and applications that continuously shift, morph, and change. As such, the fascination with a certain technology might fade in favor of a search for meaningful applications, but the fascination with technology itself will remain. The history of innovation cycles substantiates this point, hinting that the transition from the digital towards the post-digital is not a uni-directional trend but rather a cycle that every new technology undergoes from early adoption (the digital) into mature utilization (the post-digital).

If there was an architecture of the metaverse - which I claim is still to emerge - it would first appear within the “digital” before it could ever mature into the “post-digital”. Yet despite its infancy, the metaverse comes across as an adolescent proposition, not a childish one. The metaverse’s technology may be digital, but its character and personality are rooted in the cyberpunk tradition, where the future and the past blend into a single experience of broad present, randomly combining bits and pieces of actual locations, mixed and virtual reality, in no particular order. In its rebellious genesis and despite its youth, the metaverse reveals the geometry of power and instantly forces us to directly confront ideology in a way that (post-)digital architecture took longer to do.

Virtual Reality

As much as virtual reality brings up a set of philosophical problems, it also has the potential to illuminate old philosophical questions. “Virtual reality is the best technological metaphor for conscious experience we currently have” writes German philosopher Metzinger. With technological augmentation and the externalization of the human cognitive process, the new unconsciousness is in continuous and direct communication with consciousness, away from the psychoanalysis of Lacan and Freud. Virtual reality requires us to constantly switch between being present and looking at our-selves from the outside. In doing so, one asks: where does reality end and virtuality begin?

Yet, according to Gilles Deleuze, the question is flawed. The virtual cannot be opposed to the real or else we fall into tautology. The virtual does not exist in opposition to the real, but rather in opposition to the actual: the world of real extended objects. For Deluze, “since the virtual and the actual both exist in reality, the transition from one to the other implies a change in kind; a differential change from one mode of reality to another i.e. a creative act.” Thus, actualisation of the virtual is creation, and creation is determined by a process of differentiation that neither resembles the starting point, nor constitutes an act of theological unfolding.

Koo Jeong A’s augmented reality artwork Density (2019) invites us to participate in such an actualization process. The piece, a virtual reality icecube that hovers in the air in a hidden garden of Regent’s Park, London, can only be seen with the right device, and reflects its surroundings in a fully responsive manner. “The virtual does not make place and physical location irrelevant, but rather asks of us to conceive of it differently, not as a given, something already there, but as the result of operations that produce a localization, which does not make it any less real” writes philosopher Sven-Olov Wallenstein in his commentary of Koo Jeong A’s piece.

Density is a virtual mirror that draws from actual objects and reflects back into them, inviting the viewer to experience new ways of inhabiting space and time where the borders between actuality and virtuality blur for a few seconds at a time.

Andres Reisinger’s Hortensia chair is another example of actualization through the process of creation, but with opposite directionality. Reisinger designed a digital three-dimensional armchair covered with geometric pink petals, wanting to capture “the feeling of blooming flowers.” Originally intended as a digital artefact, the virtual object went viral, with strong demand for its physical representation. The chair ultimately went into production, with a limited-edition selling out through a gallery in Milan, at around 30,000 euros per piece.

Reisinger’s virtual hortensia chair was actualized through physical production and will exist in the actual world, but only as an imperfect copy of the original virtual object. The virtual simulated itself in the actual world, it actualized in the opposite direction that we are used to, reversing the ontological hierarchy that places actuality above virtuality.

Koo Jeong A’s Density and Reisenger’s hortensia chair manifest two different ways in which reality - the actual and the virtual - can be augmented, blurring the boundaries between the material and the imaginary. Reality and virtuality do not exist separately any more, but in a constant and increasing dialogue of re-invention, layering and augmentation.

Blockchains and NFTs

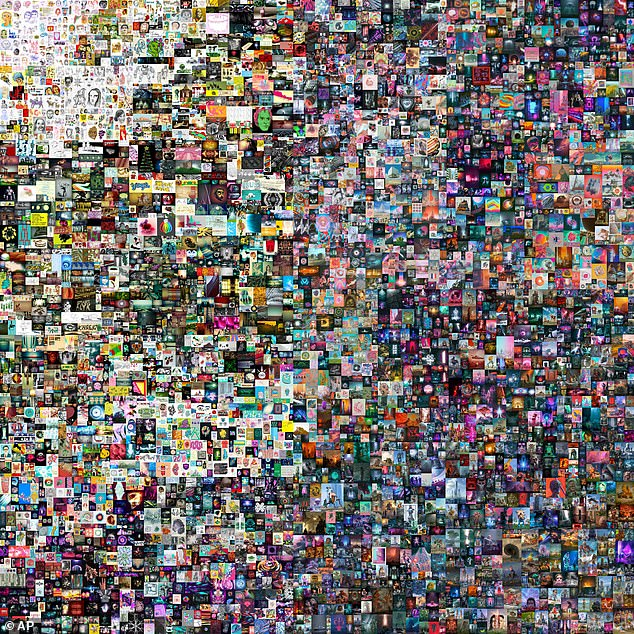

In February 2021, a 10-second video by an artist named Beeple sold online for $6.6 million. Around the same time, Christie’s announced that it would be selling a collage of 5,000 “all-digital” works by the Wisconsin-based artist, whose real name is Mike Winkelmann. It was put on a virtual auction block with a starting price of $100 — and on March 11 it sold for a staggering $69 million. In the first 10 minutes of bidding Christie’s had more than a hundred bids from 21 bidders and we were at a million dollars.

Beyond the high prices, one key fact made these transactions different from previous art auctions: in exchange for their money, collectors didn’t receive any physical manifestation of the artwork. Instead, they receive an NFT (non-fungible token) attesting the originality of the piece and the “reality” of each owner’s version.

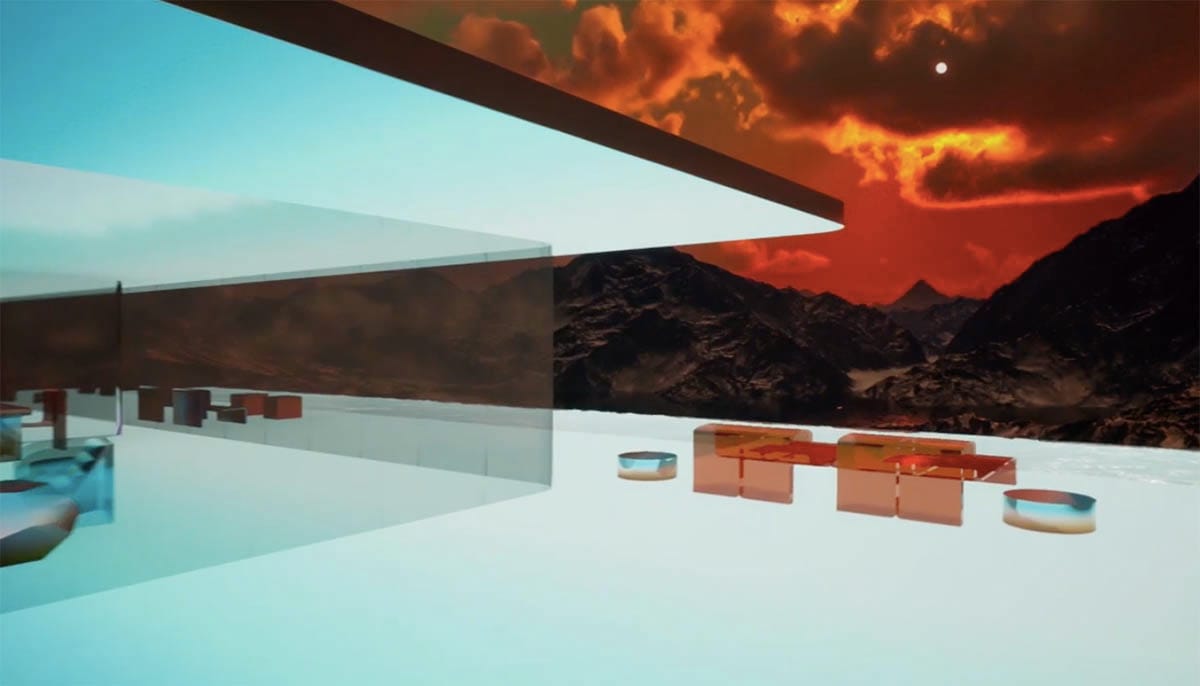

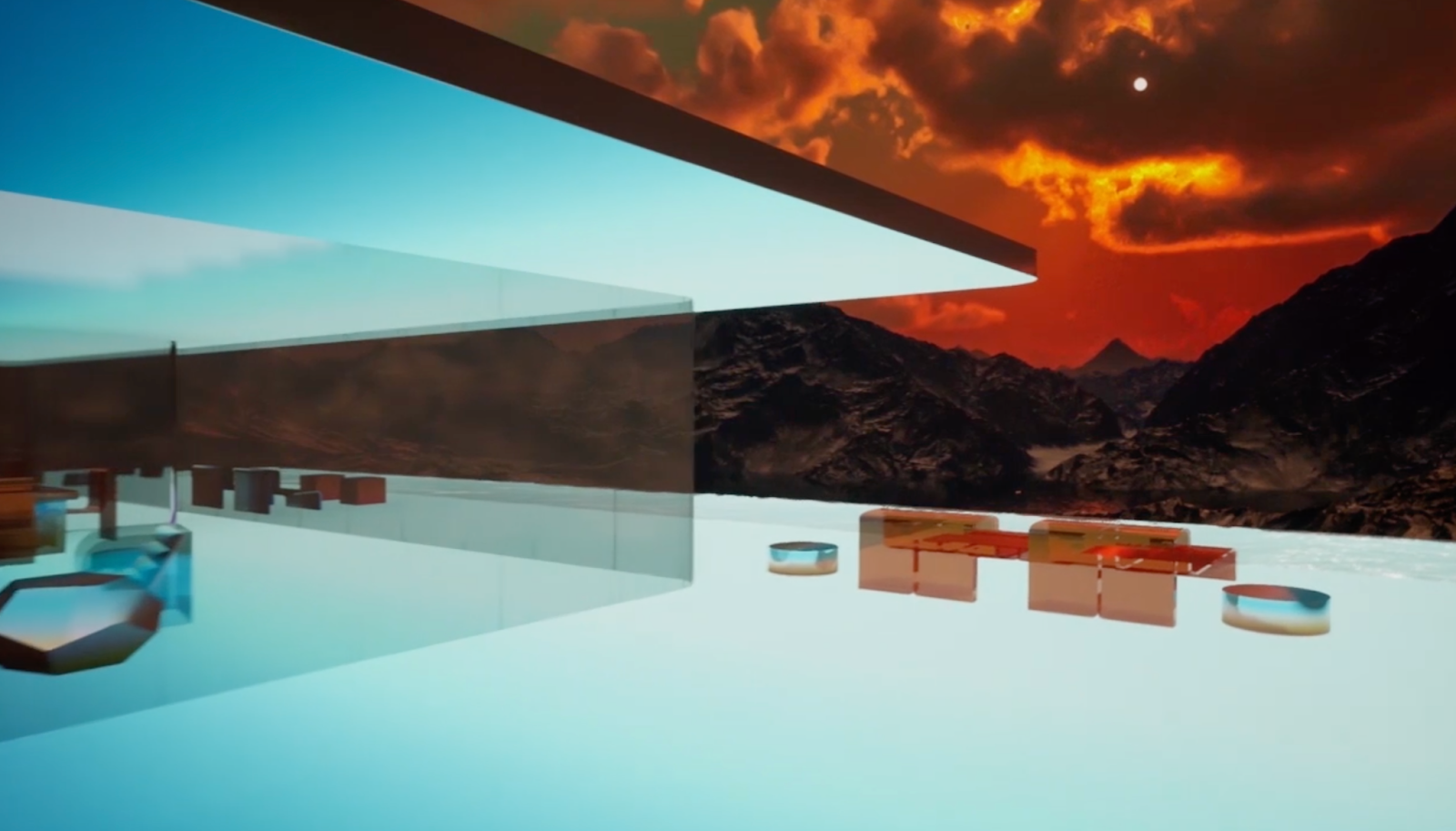

The NFT frenezy is not only disrupting the digital Art world. In April 2021, Mars House, a virtual house designed by digital artist Krista Kim sold for 288 Ether - equivalent to $514,557 at the time. In exchange, the buyer received 3D files to upload to his or her metaverse. This is not a one-off event. Over the past few months, a number of investment firms have been acquiring digital land in worlds such as Sandbox and Decentraland, where players simulate real life activities such as shopping or attending a concert.

Why are NFTs gathering so much attention? One can think of NFTs as internet-native property rights, a new type of internet primitive or building block. Commonly, NFTs are used as certificates of authenticity for digital artifacts that allow anyone to track them as they’re created, sold, and resold. Because they use smart contract technology, NFTs can be set up to pay the original artist a percentage of all subsequent sales, or to execute new types of revenue splits amongst creators and owners - past, present and future - of the asset.

To grasp the power of NFTs, one has to understand blockchain as its underlying technology. In the most traditional sense blockchains are distributed networks that provide a way to send information - often money, but not only - without an intermediary. With the advent of smart contracts which are turing-complete blockchains have now become decentralized globally distributed computers that are self-governed by their own code through a community of users with aligned incentives. Because the code is what rules the behavior, blockchains are “much more reliable than humans at doing what they committed to do in the first place [...] and can be relied on and trusted in ways that human-governed computers can’t.” These new computers have traits that old computers didn’t have, which is why the blockchain community is so excited about the possibility of new algorithms, new design rituals, new governance structures, new collectives, new visions.

Besides creating new markets and ownership structures, NFTs change the ontology of virtual reality. Until recently, virtual reality offered infinite habitable space, stacked randomly and in isolation. Virtual places in isolation are fun to explore, but spiritually rather unattractive: if multiple people can inhabit exactly the same space through multiple virtual copies yet remain disconnected from one another, how can we weave a collective experience from our individual existences? This unbounded virtual infinitum had a tendency to create detachment, loneliness and segregation. NFTs change this paradigm by creating an artificial scarcity mechanism for digital assets. In doing so, NFTs add an ontological uniqueness that actualizes - to use Deleuze’s terminology - the otherwise infinite possibilities of the digital.

Beyond the blockchain’s power to anchor virtuality in the present, the blockchain also anchors the past within a continuous universal record-keeping system that acts as a shared Recorded History. A truly persistent immutable digital index linking the past and the present in an unequivocal way. This crushing sense of history further anchors the multiplicity of possibilities, reinforcing the new ontology.

Last but not least, NFTs add interoperability to the otherwise siloed virtual worlds, allowing owners to move digital ownerships - including individual digital identities - from one virtual platform to another. The original internet left out digital property rights, forcing users to replicate - and give away - multiple digital identities across different platforms. The current social media esquizofrenia can in large part be linked to this fragmentation of identities. With NFTs, digital identities can be unified and made portable. Most importantly, they belong to each individual user, not to the platforms.

By virtue of its supply constraining mechanism, NFTs are able to anchor individual virtual spaces and assign each of them an ontological uniqueness; and by virtue of its inherent interoperability, they can now bring all of these spaces together into a continuum, the so-called metaverse. A new digital spatial ontology emerges, a space that is both computable - given its inherent digital nature - but also computing: can read and operate code directly.

Toward a three dimensional interface

The interface by which we interact with the metaverse is important both aesthetically and functionally. Editors David Berry and Michael Dieter in their introduction to the essays compilation Thinking Postdigital Aesthetics invite contributors to think about interfaces as both “an aesthetic and a locale of design thinking [...] that is also a site in which a symptomology can be deployed to raise questions about our contemporary situations, and to explore ways in which concepts and ideas, theories and statements, aesthetics and patterns are circulation around the computation as such”. In other words, the interface, beyond being a canvas and an aesthetic in and of itself, is also a tool that allows us to project and manifest questions about our time.

The first computers provided a simple interface: the command line - a one-dimensional semantic structure, where characters followed one another to produce a sentence in a computational language that could then be read, interpreted, and enacted by the computer into a non-equivocal operation.

With the invention of the mouse and higher definition screens, the command line gave place to two-dimensional operating system interfaces where the mouse and the screen provided freedom to navigate a flat space. David M. Berry in his essay “The Postdigital Constellation” alludes to the dominance of digital surfaces and how this “interface-centricity” has expanded beyond the screen, inferring a flatness which is still present in much of what is created and consumed today.

Virtual reality headsets and controllers were able to unlock a three-dimensional interface that allowed users to both design and experience objects and environments in 3D. The blockchain (and NFTs) in turn has added a temporal and individualization component, a record-keeping system that guarantees the fidelity and security of a record of data and generates trust without the need for a trusted third party. Together, they form the metaverse interface: a portal into a virtual space that is programmable and programing.

These interfaces did not replace one another. Instead, they build on each other in a complex modular continuum of protocols, algorithms, and layers, built on top of silicon and electrical signal devices - what is technically referred to as the metaverse “stack”. If this sounds very much like the inner guts of a computer, it is because the metaverse is indeed a computer: a distributed spatial computing resource made out of layers of both hardware and software that can be interacted with in a way that is natively 3-dimensional.

The stack not only provides a sense of historical cohesion, but also directionality towards the future, towards a stack that is yet to emerge. I like the way that Benjamin Bratton describes this concept in his essay The Black Stack: The Black Stack “is to the Stack what the shadow of the future is to the form of the present. The Black Stack is less the anarchist stack, or the death-metal stack, or the utterly opaque stack, than the computational totality-to-come, defined at this moment by what it is not, by the empty content fields of its framework, and by its dire inevitability. It is not the platform we have, but the platform that might be.” The metaverse can therefore be described as the stack-to-come that has arrived.

The depth at which one operates within the stack is directly correlated to the amount of control a designer will have. Those who decide to only interact at the interface level will only be able to operate within pre-defined geometries and power structures. Those willing to go down to the underlying infrastructure level will be able to directly design and codify new computing spaces.

From interface to infrastructure

In order to fully participate in the metaverse we need to move past the fascination with the virtual reality interface, and start thinking about the possibilities of this new virtual infrastructure space.

Keller Easterling, architect and professor at Yale, studies the relationship between architecture and the larger systems that dictate where and when architecture might exist. Her latest work focuses on the challenges around designing infrastructure space, understood as the fabric surrounding everything that we perceive as objects, “the matrix in which individually crafted objects float.” The use of the term float is particularly relevant in the context of virtual reality, where gravity is at most a legacy feature if not a bug, and in any case not a necessary boundary condition. Easterling calls for a new approach to design, what she calls medium design, understood as “a design strategy to respond to the powers of infrastructure space and rehearse alternative practices of design” where designers are urged to “turn away from the singular object form to work with active forms, dispositions of settings, undeclared information, and seemingly invisible organization”. Her description seems particularly fitting for the study of the metaverse. Even her understanding of the dynamic nature of reality as “an updating platform unfolding in time to handle new circumstances, encoding the relationships between buildings, or dictating logistics” can be directly applied to the metaverse.

What infrastructure space will we need to develop within the metaverse to augment and enable new cultural, social and political interactions?

Architects wishing to engage in the metaverse will need to move past the fascination for the design of virtual objects and environments. That is, if they want to have a say in the writing of the rules that will govern such spaces. The political dimension of Easterling’s infrastructure space is directly applicable to the metaverse. However, the toolkit required for metaverse medium design is slightly different that the one needed for physical medium design. When space is essentially computational, infrastructure designers need to start thinking as coders.

Architects as spatial coders

Architecture, as it relates to the built environment, has had little say in the construction of the internet to date. It is no accident however that those who designed the web communication protocols, privacy keys and information systems see their role as architects. The word “architecture” has its origin in the Greek words archi - those who command - and tecton - mason or builder - which is in turn rooted in the Proto-Indo-European word teks meaning "to weave" or "to fabricate”. It is no surprise then that computer scientists borrowed the term “architect” to describe the role of those who organize the components that make up a computer system and the semantics of the operations that guide its function. Computer architecture is defined by an instruction set - a language, a set of rules - and operand locations - registers and memory, the fabric where such operations are recorded. At its purest, rules (language) and fabric (malleable material that acts as memory) can also describe the act of architecture: a set of design processes and design language that is applied onto a malleable environment resulting in a built entity that acts as a memory of such a process. It also points towards the inherent materiality and geometry of computers themselves, and the fact that ultimately, compute activities happen in space somewhere.

In this new spatial computer that is the metaverse, architects can decide to remain on the surface, designing aesthetically engaging virtual objects and spaces, or they can step up to spatial coders, designers not only of the objects within the metaverse but of the spatial infrastructure that is the metaverse. If the work of architecture is to augment and supplement human life for a better future, a purely aesthetic approach to virtual design will be way too narrow.

From infrastructure to politics

The internet as we know it today, the so-called Web2, consists of services that are siloed and centralized, with most of the value being captured by a handful of companies like Google, Apple, Amazon, and Facebook. Within these platforms, humans interact less as citizens of a polis or as homo economicus within a market, and more as users - eyeballs that can then be sold, re-hashed and fed again into the system.

This was not always the case. The first incarnation of the internet - between 1990-2005, what is today known as Web1 - focused on open protocols that were decentralized and community-governed. Most of the value accrued to the edges of the network — users and builders. In this sense, the first incarnation of the internet was activist in nature, a grass-roots movement.

Yet as the internet became ubiquitous and closed platforms gathered strength, political conversations were pushed out of the infrastructure and protocol layers onto the superficial app interfaces: politics continued to be discussed, but only within siloed online forums that served as echo chambers within closed platforms owned and operated by private corporations with their own political agenda, often very misaligned with those of their users and audiences. Web2 was born.

Easterling’s point about the dangers of ignoring the forces at play is yet again relevant here: “It is wildly dangerous to rely on declared ideology, when undeclared forces often facilitate untouchable accumulations of power and environmental forms of violence”. Pushed to the limit, Web2 threatened to turn the city of tomorrow into a digital schizophrenia: “In a condition of growing superimposition between digital and physical, the threshold of the real is being pushed by a vast set of apps and platform that as a wired-wiring infrastructure manipulate cities and citizens in a constant exchange of data; in turn, this is progressively invading and exceeding the set of references we have to describe the urban condition” writes Federico Ruberto in his review of the 2019 Shenzhen Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (UABB), titled Urban Interactions. Taken to its extreme, Web2 users become mere data producers and collectors within spaces whose sole purpose is to provide monetization venues.

It is no surprise then that self-governance and re-alignment of incentives has been at the core of the blockchain project since its inception as a direct reaction to Web2. The blockchain layer fully changes the power dynamics of the internet. The blockchain-enabled internet - the so called Web3 or metaverse - combines the decentralized, community-governed ethos of Web1 with the advanced functionality of Web2. Before Web3, users and builders had to choose between limited functionally and open source, or corporate, centralized offerings. Now they can have the best of both worlds, opening up the possibility for new spatial and temporal models of politics and publics.

At the core of Web3 is an activist agenda to free Web2 users from their consumer only role and grant them citizen status through governance rights. Such government rights have found their most successful incarnation in decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs). DAOs are entities built as blockchains that live on the internet and exist autonomously, with no central leadership. In DAOs, decisions get made from the bottom-up, governed by a community organized around a specific set of rules enforced on the blockchain. DAOs are self-governed communities, some of them with geo-political aspirations. CityDAO for instance aims to create entirely new cities from scratch, making heavy use of radical economic ideas like Harberger taxes to allocate the land, make collective decisions and manage resources. Their DAO is recent but has already started buying empty lots in Wyoming. Much more advanced is the Decentraland project, a virtual world owned by its users and also controlled via a DAO. Through the DAO, owners-users decide and vote on how the virtual world works.

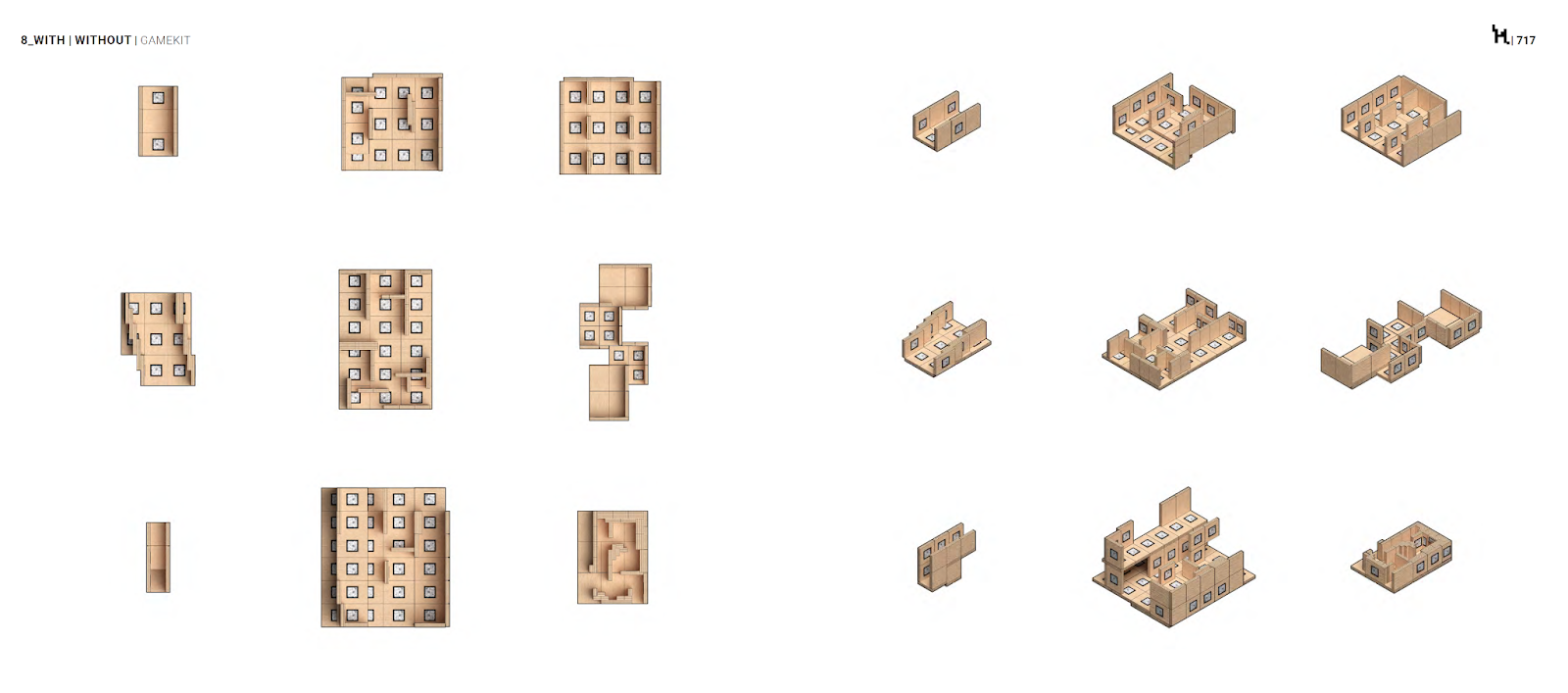

Nothing prevents these governance systems from being applied at smaller neighborhood or multi-family living scales. “With/Without”, a thesis project from graduating students at the UCL Bartlett School of Architecture in London, explored the power of communities to design built environments using prefabrication and robotic assembly techniques. In the project, multiple users come together within a gamified experience to express their living space needs and negotiate their spaces within a set of geometrical and fabrication constraints.

The project, which didn’t make use of Web3 technology, could have been enhanced by it at multiple levels. For instance, a DAO governance structure where each individual owned a number of tokens within the DAO could have allowed participants to anonymously and securely share their desired design, have a say and vote on the boundary conditions used for negotiation, and ultimately participate in the success of the project as a whole (thanks to their percentage ownership in the development). Upon completion of the design, an NFT could have provided to each participant with a unique, transferable indentier of their spatial ownership which could then have been traded on an open marketplace to provide liquidity for owners and a way to upgrade or downgrade their living units when circumstances changed. A virtual interface could have helped optimize building blocks, rules and final design, all with the participation of users. A gamified virtual representation of the work-in-progress building design could allow users to virtually meet future neighbors on site and better negotiate private and public boundaries.

These are just a few examples but I hope they illustrate the potential of the metaverse to enhance and unlock new design paradigms.

It is not surprising then that sectors of the Web3 community are becoming increasingly interested in the power of DAOs and virtual environments to augment and improve the city as our primary unit of collective living. Vitalik Buterin, founder of the Ethereum network and one of the brightest minds within the blockchain community, in an essay titled Crypto Cities recently reviewed multiple blockchain projects on the city and laid out several potential implementations of NFT and DAO systems to improve or drastically re-invent the city.

Although very incipient, each and every one of these projects points us towards a potential alternative future. We don’t know which ones will survive. What we do know is that the future will be rich and complex, multi-linear and mixed, reliant on augmented-devices that codify the physical world so that machine-learning algorithms can compute and enact operands within hybrid spaces in a never-ending feedback loop between the actual and the virtual.

Closing remarks

You are designing not only a single object but a platform for inflecting populations of objects or setting up relative potentials within them. You are comfortable with dynamic markers and unfinished processes. – Keller Easterling

The geometry of reality as we know it is about to be changed. Reality will become deeply hybrid, in a perpetual feedback loop between the actual and the virtual. Ontologically, we will become comfortable navigating and constantly crossing those boundaries, just like we have with previous technologies. Yet, the computational nature of this new interface will require architects to understand and master a new design language: governance protocols, NFT smart contracts, shaders and meshes, real time renderers, and their virtual and physical implications. “Designed spatial stories will be operations that involve queering the physical with the digital and the digital with the physical, genders with genders, and categories with categories” writes Federico Ruberto. In designing such “operations” architects will have to become coders of computing space.

Collectively, we shall cherish and protect the open nature of this new spatial operating system. We well know how easy it is to lose it.

Bibliography

Ariso, Jose Maria, ed. Augmented Reality. Berlin De Gruyter, 2017.

Andersen, Christian Ulrik, Geoff Cox and Georgios Papadopoulos, ed. Postdigital Research, APRJA Vol. 3 No. 1 (2014)

Ball, Matthew, “Framework for the Metaverse: The Metaverse Primer,” MatthewBall.vc Personal Blog (Jun 2021).

Berry, David M. and Michael Dieter. Postdigital Aesthetics - Art, Computation and Design. Palagrave Macmillan, 2015.

Birnbaum, Daniel, “Ontologies of the Virtual. Interview of Sven-Olov Wallenstein on Koo Jeong A.,” e-flux Journal (2019).

Bluemink, Matt, “On Virtuality: Deleuze, Bergson, Simondon,” Epoque Magazine, no. 36 (Dec 2020).

Bosco e Silva, Luciana, Andressa Martinez and Carlo Castriotto, “The diagram process method: the design of architectural form by Peter Eisenman and Rem Koolhaas,” in Architecture and Writing, Dakam Publishing, 2014 (pp.483-491).

Bratton, Benjamin H., “The Black Stack,” e-flux Journal, no. 53 (March 2014).

Buterin, Vitalik, “Crypto Cities,” Vitalik.ca Personal Blog (Oct 2021).

Catlow, Ruth et al., ed. Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain. Torque Editions & Furtherfield, 2018.

Cao, Shuyi and Remina Greenfield, Ross M. McBee, “As If They Were Thinking: New Aesthetics of ‘Thought’ in Machine Intelligence”, decompose.institute.

Chalmers, David J., ”The Virtual and the Real,” Disputatio 9 (46):309-352 (2017)

Chalmers, David J. Philosophy of Mind: Classical and Contemporary Readings. Oxford University Press, 2002.

Clayton, Mark, “A Post-Digital Architectural Research Agenda to Address 21st Century: Challenges,” Technology|Architecture + Design, 1:1, 16-18.

de Donato-Rodrguez, Xavier, “Construction and Worldmaking: the Significance of Nelson Goodman’s Pluralism.” THEORIA. An International Journal for Theory, History and Foundations of Science, no. 24 (2), 2009.

del Aguila, Santiago and Argyrios Delithanasis, Andrea Terceros and Ghanem Younes. With/Without. Thesis at UCL Bartlett School of Architecture, 2021.

Derrida, Jacques. Of Grammatology. Translation by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. The John Hopkins University Press, 1974.

Dixon, Chris, “What is Blockchain: Computers That Can Make Commitments” Andreessen Horowitz company blog (Jan 2021).

Dixon, Chris, “Why Web3 Matters,” https://future.a16z.com/ (Oct 2021).

Dourish, Paul, The Stuff of bits: An essay on the materialities of information. The MIT Press, 2017.

Durham Peters, John. The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media. The University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Easterling, Keller, “Medium Design.” e-flux journal, no. 106 (February 2020).

Easterling, Keller. Medium Design: Knowing How to Work on the World. Verso Books, 2021.

Graafland, Aerie and Dulmini Perera, ed. Architecture and the Machinic - Experimental Encounters of Man with Architecture, Computation and Robotics. Titel: DIA Series, Volume Nr. 11, 2018.

Gomel, Elana. Recycled Dystopias: Cyberpunk and the End of History. Special Issue Cyberpunk in a Transnational Context in Arts, 2019.

Goodman, Nelson. Ways of Worldmaking. The Harvester Press, 1978.

Hayles, Nancy Katherine. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. The University of Chicago Press (1999).

Heim, Michael. The Metaphysics of Virtual Reality. Oxford University Press, 1994.

Jencks, Charles and Karl Kropf, ed. Theories and Manifestoes of Contemporary Architecture. Academy Editions, 1997.

Jacob, Sam, “Architecture Enters the Age of Post-Digital Drawing,” Metropolis (March 2017)

Kolarevic, Branko. Post-Digital Architecture: Towards Integrative Design. First International Conference on Critical Digital: What Matters(s)?, Harvard University Graduate School of Design, Cambridge (USA), 2008.

Kolirin, Lianne, “World's first digital NFT house sells for $500,000,” CNN (March 2021).

Magnenat-Thalmann, Nadia and Daniel Thalmann. Artificial Life and Virtual Reality John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 1994.

Metzinger, Thomas K., “Why Is Virtual Reality Interesting for Philosophers?,” Front. Robot. AI (Sept 2018)

N.a., “Virtual on Actual: Augmented reality and contemporary worlds,” Bristol Society and Space (Dec 2017).

Papamattheakis, George, “Inside Keller Easterling’s personal medium design: An interview with Keller Easterling,” StrelkaMag (Sept 2019).

Picon, Antoine, “Beyond Digital Avant-Gardes: The Materiality of Architecture and Its Impact,” Architectural Design (September 2020).

Putzier, Konrad, “Metaverse Real Estate Piles Up Record Sales in Sandbox and Other Virtual Realms,” Wall Street Journal (Nov 2021).

Rantala, Juho, “The Notion of information in early cybernetics and in Gilbert Simondon's philosophy,” Doctoral Congress in Philosophy Tampere University, Tampere, Finland (Oct 2018).

Rossiter, Ned and Soenke Zehle, “The Experience of Digital Objects: towards a Speculative Entropology,” Spheres: Journal For Digital Cultures, no. 3 (2017).

Ruberto, Federico, “Latent Cities with Eyes Wide (and) Shut” ArchDaily (March 2020).

Ruberto, Federico, “Models and Fictions. The Archi-tectonic of Virtual Reality,” in Virtual Aesthetics in Architecture: Designing in Mixed Realities, edited by Sra Eloy, Anette Kreutzberg and Ioanna Symeonidou. Routledge, 2022.

Russ, Legacy. Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto. Verso, 2020.

Sheil, Bob et al., ed. Design Transactions: Rethinking Information Modelling for a New Material Age. UCL Press, 2020.

Steyerl, Hito and Department of Decentralization, and GPT-3, “Twenty-One Art Worlds: A Game Map,” e-flux Journal, no. 12 (2021).

Till, Jeremy, Money. The Economies of Architecture. Rosenberg & Sellier (2018)

Vindenes, Joakim and Barbara Wasson, “A Postphenomenological Framework for Studying User Experience of Immersive Virtual Reality”, Frontiers in Virtual Reality, Hypothesis and Theory (Apr 2021).

Weisberg, Michael. Simulation and Similarity: Using Models to Understand the World. Oxford University Press, 2013.

Zhai, Philip. Get Real: A Philosophical Adventure in Virtual Reality. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1998.